A Go Browser Battle

I learned Go from my Dad — after all, we lived in Japan for a short while when I was little — but DeepMind’s foray into the venerable board game definitely renewed my interest.

My friend Jan, also intrigued, had started working on a browser-based interface to play the game.

So I offered him a playful challenge: we would both try to build an interesting AI for the game, and we would pit them against each other.

Each AI would be in a separate WebWorker.

At each turn, they would receive the board state.

They would have one minute to come up with their move, in a best-of-five tournament.

From what he told me, Jan will be trying to brute-force the search tree with a traditional minimax.

He is betting on a smart and fast board evaluation.

As for me, I started studying the AlphaGo Nature paper.

I took machine learning classes at University; time to apply what I learned!

I definitely don’t have the computing power or the time to reach the level that AlphaGo achieved.

It took months of training and self-play on tens of GPUs and hundreds of CPUs.

My dream is to reach 1d; a rank roughly equivalent to a black belt in martial arts.

Stepping Stones §

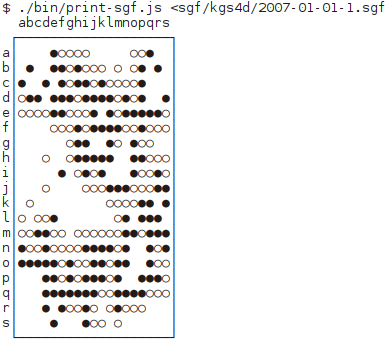

Go games are typically saved as SGF files, which are plentiful on the Web.

Therefore, the first step I needed to achieve was to have an SGF parser and a Go execution engine.

The engine is designed to give me a wealth of information about the game: what group is a stone part of, how many liberties that group has…

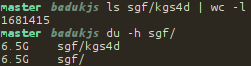

I downloaded all KGS games involving players that are 4d or above.

I hope my design achieves 1d, so in principle, the AI will never reach that level of play.

Aside: I think it is interesting to think about learning in terms of training capacity and model capacity.

Here, since we learn to mimick the moves of the training set, the AI can only be as smart as the training set, which puts a limit to how intelligent it can be.

But the model itself can achieve a superior level through self-play (which is what DeepMind did, obviously, since they reached a level beyond the top human player). Then, the level they can achieve is that of the model capacity.

An entity able to perfectly analyse all possible futures would have the highest possible model capacity.

The KGS dataset represents 1.7 million games.

After rotating and reflecting each game, I should reach 13.5 million games, which should be enough to teach the neural network.

Just like AlphaGo, I will first train a move guesser using a convolutional neural network.

That network reads the board through a hundred lenses called “filters” that focus on 3x3 squares (or 5x5 on the first layer).

Each lens annotates every intersection with an analysis of its surroundings.

The annotated board is given as input to a different set of lenses, and so on, ten times.

The last annotated board rates the moves with how likely KGS players are to make them.

The move guesser can be used standalone, although I don’t expect it to perform well.

Its main purpose is to limit the number of moves you will look at on the search tree.

Expanding too many nodes can really make your AI lose precious time.

I also want to train a win guesser. It is another convolutional neural network.

Instead of yielding likely moves, it will tell you who it thinks will win.

While AlphaGo trained its win guesser from self-play games which also improved its move guesser, I am unsure whether I will have enough time to implement self-play tournaments.

But having a win guesser learn from the KGS data set is possible; it simply might yield poor results.

Finally, if I have time to spare, I may implement Monte-Carlo Tree Search (MCTS).

It requires having a very fast move guesser (not the 10-layer monster).

AlphaGo trained a shallower neural network for that purpose, feeding it, in addition to the board state, whether a given move matches a set of well-known patterns.

The paper claims it guesses about 24% of moves from their data set, at a meager 2 μs.

For this purpose, I am tempted to perform some custom statistical analysis on the training data.

Yet again, it depends on what that yields, and how much time I have.

MCTS works by repeating the following steps:

- walk the tree through what is currently the best move,

- without adding nodes to the search tree, play with the weak move guesser until the end of the game,

- update the node’s ancestors in the search tree to count the number of wins and losses, which may change what is the best move.

When a node is walked through enough times, it gets expanded with the strong move guesser.

Into The Browser §

I plan on training the networks in Python with Keras, which will use TensorFlow to benefit from its optimized C++ engine.

I own a desktop computer that unfortunately features a weak-ish Nvidia GPU, but it will have to do!

Keras is fast becoming the standard API to train and export neural nets; Microsoft recently touted its support as a front-end for CNTK when they unveiled version 2 of the library.

Inevitably, there are a couple libraries to convert Keras models to JavaScript.

Keras.js most notably features GPU support, but using the GPU in a WebWorker is not yet possible.

Maybe when all browsers implement OffscreenCanvas and Keras.js implements support for it?

And there’s WebDNN, which I will use.

WebDNN is fastest when using WebGPU, a standard that I hope will get traction, but that is currently Safari-only.

However, it can compile the neural network to WebAssembly, which should fit in a WebWorker.

Dreams and Work §

This will all be a free-time effort.

There is no planned date for the final confrontation.

The code for the SGF parser, Go engine, and AIs will be here, and the UI code will be there.