How to implement Go

As I wanted to make an automated Go player, as I planned on a previous

article, I first needed a full implementation of the game

of Go.

Go is a beautiful, tremendously old game with very simple rules and yet

tremendous subtlety. Here are the rules:

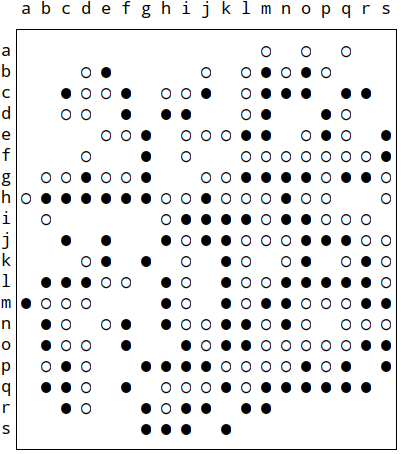

- Each of two players, black or white, take turns either passing or placing a

stone of their color on an intersection of a 19×19 board, starting with

black.

- A group is a set of stones that are next to each other (up, down, left or

right), or next to a stone that is in the group. A group’s liberties are

the number of disctinct empty intersections next to the group’s stones. When

a player places a stone, all enemy groups that no longer have any liberties

are captured: they are removed from the board.

- A player is not allowed to place a stone if it causes the start of next turn

to include a group with no liberties. That forbids suicides.

- A player is not allowed to place a stone if it causes the start of next turn

to have a board configuration that already occurred during the game. This is

known as a Ko when the configuration happened on the previous turn, and

as a Superko more generally. It ensures that games must end; there are no

draws.

- When nobody can add stones, the player with the most stones, enclosed

intersections (aka. territory), captured stones, and Komi (an added

bonus to white to compensate for the asymmetry of who starts first), wins.

The Komi usually has a half point to ensure that there can be no equal

scores, again to forbid draws.

The board §

Since the board is a compact 2-dimensional space, we use an array, with each

slot containing an intersection which includes its state (empty, with a white

stone, etc.) and historical and analytical information for use by the learning

systems: whether it is a legal move, when it last received a move, whether it is

the atari liberty of a group, ie. the move that captures the group, and how

many stones it captures.

We also keep track of all groups on the board. Each intersection links to its

group, and the group maintains a set of its stones, and another of its

liberties. When registering a move, groups are updated. It is fast, since at

most four groups may need updating.

There is some logic to merge groups together, destroying the original groups,

and creating a new one that contains the union of the previous ones. It is not

particularly fast (and could likely be improved by keeping the largest group and

adding the others to it), but since merging groups does not happen on every

turn, it did not seem to matter that much for now.

Counting final or partial points also requires maintaining territory

information. Yet again, we use a set to keep the intersections, and each move

updates the territory information corresponding to its surroundings.

Play §

The most complicated function is inevitably the logic for computing a move. We

must look at surrounding intersections and their groups, to assess whether the

move is a suicide (and therefore invalid), and when it captures enemy stones.

Most operations are essentially constant-time, apart from group merging, since

the number of impacted groups is bounded, and all operations are set updates.

Superko §

Detecting a match into previous board configurations is probably the trickier

part of the system. Fortunately, a subtle algorithm for it already exists:

Zobrist hashing.

It relies on a smart hashing system, where each possible board configuration is

mapped to a unique hash. Trivial hashes would be too slow: your first guesses

for a hash probably require to read the whole board. Instead, a Zobrist hash is

similar to a rolling hash, in that it only needs a single update to account for

the forward change.

You start with a hash of zero for the blank board. When initializing the board,

you generate a random 64-bit value (or, when you are like me and use JS, a

32-bit integer) for each intersection on the board, and for each move that can

be made on that position (place a black stone, or place a white stone).

To compute the hash for a new board configuration, you take the hash of the

previous board. For every change on the board, you XOR the previous hash with

the random value associated with this particular change.

For instance, if you place a black stone on A19 and it captures a white stone on

B19, you will XOR the hash with the random value for “black A19”, and then XOR

it with “white B19”. Fun fact: it yields the same value if you do it the other

way around.

Score §

The bulk of scoring is establishing territories. To make things simple, we

assume the game went to its final conclusion, where there are no gray zones. All

regions are either surrounded by white or black, and there are no capturable

stones left.

All that remains is to go through intersections in reading order, top to bottom,

left to right, and to stitch each empty spot to its neighbor territories,

potentially joining two larger territories together if necessary. Any stone that

is next to the territory gives it its color.

It makes counting points fairly easy: add komi, capture, stones on board, and

own territory, and the trick is done.

Ongoing §

Having implemented the game rules is not enough to properly train bots on it.

For starters, we need an SGF parser to extract information about the moves

of existing games. SGF (Simple Game Format) is the main format for serializing

Go games.

Then, we want to support GTP: the Go Text Protocol is the most common format

for transmitting remote commands between a Go implementation and a robot player.

Finally, we will explore various techniques for AI design.

Expect fun!